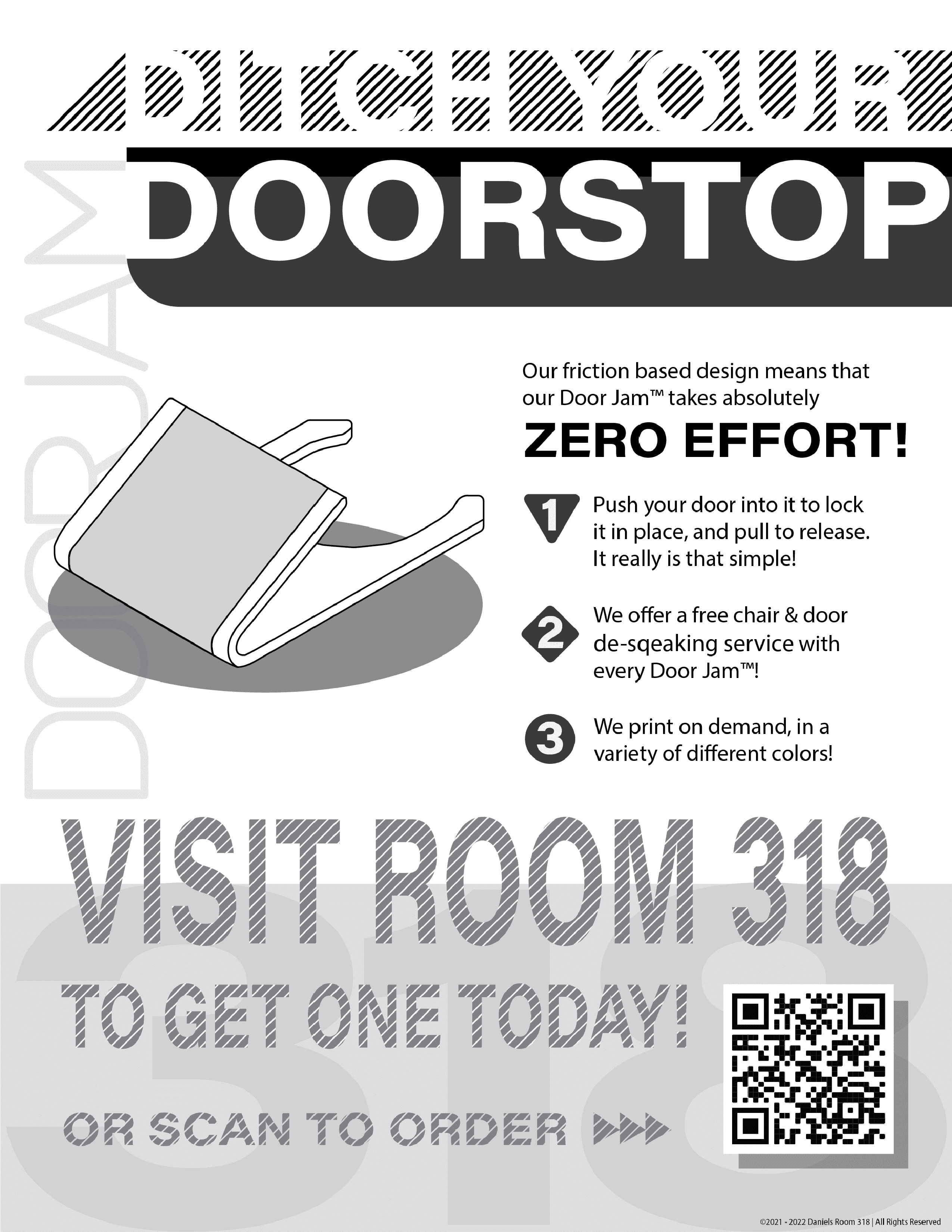

Ditch Your Doorstop: Adventures in Rapid Prototyping and Entrepreneurship

May 27th, 2024

All Good Ideas Start With a Problem

All good ideas start with a problem. In my freshman year dorm hall, the problem was that room doors wouldn’t stay open. Our dorm hall was equipped with those heavy fire-proof doors that swing close if nothing is propping them open. You really only had two options to keep one of these doors open. You could (1) wedge a door stop in the door, or (2) place a heavy object like a brick in front of the door. However, both of these solutions pose problems. Considering the weight of the door, doorstops would need to be precisely wedged into the door to actually make the door stand still. Often times kicking the stop in with your foot wouldn’t be sufficient, and you would need to physically reach down to get enough leverage to wedge the doorstop into the door. The heavy object poses a more obvious problem, that being that it’s a pain in the a** to move.

My roommate and I thought there had to be a better solution. We wanted something that was convenient, failure-proof, and (us being college students) cheap to produce. Our need for convenience drove how our idea functioned. The general solution was a mechanism that could catch the door and hold it open, but also release the door when an opposing force was applied to it. All this needed to be able to be done without the person operating the door having to bend over or squat down. Our first thought was to use magnets. But alas, magnets are quite expensive, especially in the quantity or quality we would need for these doors. Our next best idea was to use springs. One or more springs could apply pressure to the underside of the door. If sufficient force was applied to the door, and the surface in contact with the door was large enough, the door could be held in place via friction. You could move the door in and out of the mechanism laterally without much effort since the force was being applied from underneath rather than from the side of the door. Finally, this mechanism needed to minimize how many points of failure it had. To achieve this, we decided that the entire mechanism should be a single piece. This created a conflict with our spring solution, because we couldn’t keep the mechanism as one component without removing the necessary springs and possible fasteners. Our solution was to make the mechanism compliant.

Compliant Mechanisms and 3D Printing

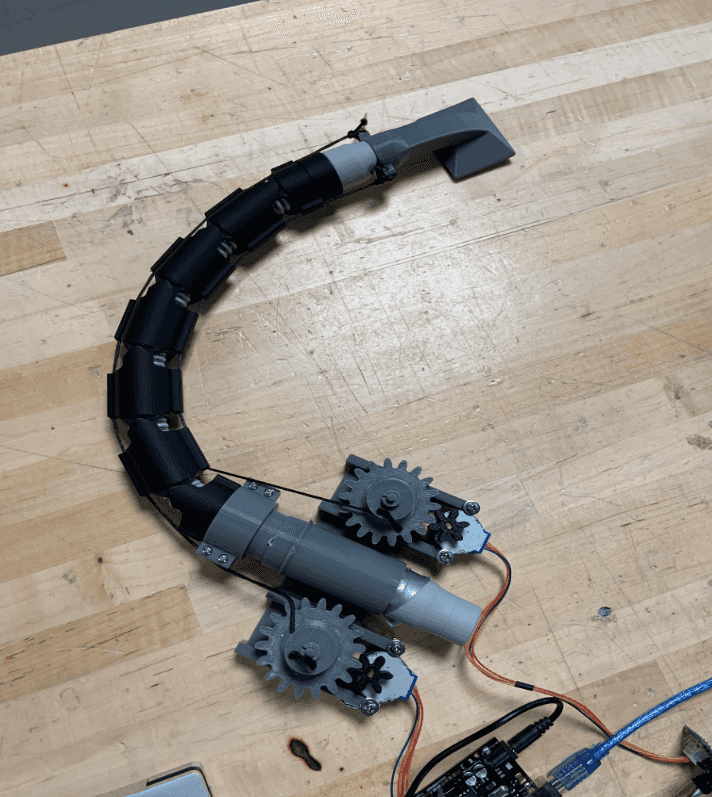

Compliant mechanisms are flexible, often single component mechanisms, which transfer forces through elastic movement rather than through the movement of rigid linkages like in a standard mechanism. We reasoned that if our door jam mechanism was made of a flexible material, it could be compressed by the door to store elastic energy. This elastic energy would exert a force back on the bottom of the door. If enough of this force was applied normal to the door bottom across a large enough area, friction would hold the door in place.

We chose to 3D print our door jam for three reasons. The first reason was that we needed the material to have the right balance between elasticity and rigidity. 3D printing the part with ABS plastic would create a part with just the right amount of flexure for our needs. The second reason is that we needed to produce a part with complex geometry quickly, while being able to make changes to that geometry if needed. 3D printing treats most geometries equally in the sense that one shape is no harder to print than another. This would allow for rapid iteration of our design. Finally, given that one has ready access to a 3D printer, 3D plastic printing is cheap. Luckily, we already had access to our campus’ 3D printing lab.

The Design

The whole door jam is simply two flat rectangular surfaces connected by a c-shaped spine. The bottom surface finishes with a circular cut out which hooks onto one of the door dampeners present in any of the dorm hall’s rooms, thereby securing the door jam in place. The top surface is angled upward away from the door. As you push the door into the door jam, the door pushes the top surface downward, compressing the c-shaped spine. At a certain point, the elastic potential from the spine causes the top surface to press on the bottom of the door with enough force to lock the door in place from friction alone. Unlocking the mechanism is just as simple. Pulling the door away from the door jam decreases the friction, allowing the door to swing closed.

The three main variables to consider in the design were the thickness of the spine, the length of the door jam, and the gradient of the top surface. These were important to consider, as the door jam needed to be able to handle the force applied by the door without permanently deforming, while also exerting enough force back to hold the door in place. To ensure the frictional forces on the door would reach their full potential, we increased the friction coefficient on the top surface by roughing it up with a coarse grit sandpaper.

The Development Cycle

Our development cycle could be broken down into three steps: prototyping, testing, and refining. In the prototyping stage we started out with a proof of concept, that being a design in our CAD software of choice. Next, we would slice that design into G-Code and 3D print it. We would test the design ourselves to see if it satisfied our requirements. In later testing stages, we printed extra door jams and gave them to our friends in different rooms to test. If we or anyone we gave a prototype to found something that could be improved, we refined the design based on that feedback and cycled back to the prototyping stage. The development cycle only concluded when all the requirements for our design were met.

The design went through six iterations. Unfortunately, I’ve lost a photo I took that shows all versions of the door jam side by side. To summarize what changes were made, the mechanism generally became thinner and shorter, yet steeper over time. Making the c-shaped spine less thick allowed it to bend more without deforming plastically. Making the top surface more angled over a shorter distance had the same effect as a less angled surface over a longer distance, yet with the advantage of saving space and material. These changes therefore cut down the amount of plastic needed to produce the door jam, cutting its production costs by around 40%. Some purely aesthetic changes were also made to make the door jam more visually appealing.

Door-to-Door Marketing

One side effect of sharing our prototypes with friends was that they all seemed to want a finalized version of one. This made us realize that our need wasn’t isolated to just us and that other people would be willing to use, and possibly even buy, our door jam. We had the opportunity to not just solve a problem but make back the money we spent developing the door jam and then some.

One of the first things any business or entrepreneur learns is that it doesn’t matter how well a product fills a gap in the market if there’s no marketing to push that product to your target audience. Technically we were marketing the door jam already through word-of-mouth. Our friends had already informed some people they knew of our door jam. Unfortunately, this passive marketing wasn’t effective enough to secure a larger audience. Instead, we decided to talk to anyone in our hall with an open door to see if they wanted a door jam. Our rationale for why this marketing strategy would be highly effective is thus: any room with an open door is not only probably more sociable and therefore easier to talk to too, but also may have a need for a better door stop to keep their door open. Any room with a closed door is not worth pitching too because they are harder to reach and probably don’t need a tool to keep their door open anyway.

We also created a promotional poster and posted copies of it in high foot traffic areas of the dorm hall like common rooms and stairwells.

Conclusion

So how many door jams did we sell? Two. However, we did give three away to some of our friends. Because our academic and social lives did take priority over this experiment, and we never realized our full potential to make a profit. Fortunately, our losses were only around twenty dollars between the two of us. It did pay (well, not exactly) to keep the design cheap.

Of course, the goal was never strictly about turning a profit. This door jam excelled at solving our problem right up until we moved out of that room in May. We gained skills in rapid prototyping and transforming an idea into a marketable product. Most importantly this project taught us that your ability to solve a problem is limited only by your initiative to do so, because idea is only valuable if you make it a reality.

Footnotes

- We used the word “door jam” to distinguish it from a regular door stop.

- There are exceptions to this rule of course, such as how FDM printers are usually unable to print steep or nearly flat overhangs in mid-air.

- You may notice on this poster an advertisement for a chair and door de-squeaking service. Many of the chairs and doors in our dorm hall were squeaky to the point of annoyance. We thought that by advertising this alongside the door jam, we may be able to sell more door jams.

Table of Contents